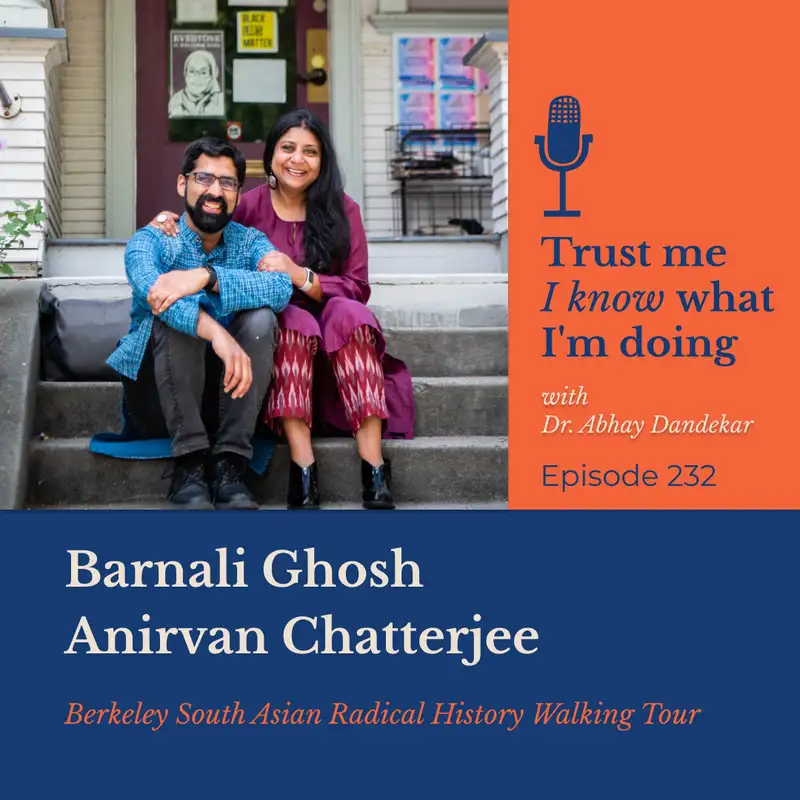

Barnali Ghosh and Anirvan Chatterjee... on the Berkeley South Asian Radical History Walking Tour

Download MP3My name is Abhay Dandekar, and I share conversations with talented and interesting individuals linked to the global Indian and South Asian community. It's informal and informative, adding insights to our evolving cultural expressions where each person can proudly say trust me, I know what I'm doing.

Hi, everyone. On this episode of trust me, I know what I'm doing, a conversation with Barnali Ghosh and Anirvan Chatterjee of the Berkeley South Asian Radical History Walking Tour. Stay tuned. Activism. It's a work in progress for many, but big and small examples are all around us.

And in just about every corner of the world, people work hard in their own ways to campaign for change. And speaking of working hard, thank you so much for listening and watching and taking time out of your day for trust me, I know what I'm doing. I know it takes time and effort, and so I'm greatly appreciative of you for engaging with me here and for sharing this with your friends and family. And if you're enjoying these and if you can support the show, please take a moment and share a kind rating or submit a written review wherever you're getting this right now. So I live near Berkeley, California, and for the past almost 35 plus years, I've gone to college here and worked here and raised a family nearby.

But along this winding path, I know that I take for granted the tireless effort and sacrifices made by generations of activists and pioneers who have paved the way in every community to fight oppression, promote fairness, and bridge gaps in awareness. And what's kind of striking is that I bet if you examined your daily life and took a look at your own routines, you too could likely trace many of the steps you take daily or things you enjoy without even thinking about it back to some demonstration of activism. So it was really great to share a conversation with Barnali Ghosh and Anirvan Chatterjee, 2 community based historians and longtime Bay Area activists who created the Berkeley South Asian Radical History Walking Tour. Anirvan is a data scientist and a techie whose work is rooted in racial and climate justice, and Barnali is an artist and designer who recently took her experiences in advocacy and local sustainable transportation to run for public office and now serves as a Bay Area Rapid Transit board director. So hearty congrats to her on her recent election.

Born from their combined thirst for social justice and a commitment to local grassroots storytelling, the Berkeley South Asian Radical History Walking Tour brings local movements and histories to life on a 2 mile walking route and is based on years of archival research and oral history, helping to inform and ground participants by unearthing a 100 years of South Asian American activism in Berkeley, recounting 4 generations of immigrant freedom fighters, feminists, LGBTQ plus organizers, and more, Barnali and Anirvan practice a rare art in sharing conversation and bringing to life histories that are not commonly taught. But their activism is not limited to just touring as they also organize the naming of a downtown Berkeley street after Kala Bagai, one of the first local immigrant activists of the early 1900. I had a chance to catch up with them a few months ago, and we talked about everything from amplifying stories to the temperament required for activism to navigating through important racial intersections around us. But as they are about to soon celebrate the 300th tour, I wanted to know if they could share some reflections and what they remembered from their very first tour. We were running a tour as part of the history curriculum for this young for this group of young activists, and they were super diverse.

I mean, they were folks from, like, Pakistan and India and Sri Lanka. They were mostly from California, but kind of all over. They had different issues they're working on, like climate change. This is, 12 years ago, like, anti Islamophobia. Just a lot of different things.

And for us, there's a thing where a lot of our history, we are told that it's always the back in the homeland. We always have to look 10000 miles away to, like, know where we came from. And there is so much South Asian American history, so many stories, just like on the streets you walk on. Yeah. And we know this just from, like, being, like, not 15 or 20 years old.

Right. And living in Berkeley, and I've been living in Berkeley since 19 nineties. I mean, we could be doing this tour anywhere. We just happen to live in Berkeley. It was really important for us to kinda get across to a lot of the young activists.

Like, you don't have to invent this. We have in the same way that, yes, we have a tradition of arts, we have a tradition of music. For better or for worse, we have a tradition of certain kinds of professions, of those who have been graded here first. We can actually tell a much larger story of who we are through a story, and that meant that we were able to tell stories of anti colonial activists who were, like, living and running around in Berkeley a 100 years ago. We were able to tell stories of post 911 solidarity.

We're able to tell stories of, like, black and brown standing together. And for some of these young people, I mean, it was just, like, we're all changing Mhmm. To know that their world is a little bit bigger than, like, the version of South Asia that their parents had told them. Yeah. And half a block from where the campus happening is where we started the tour.

So they are in this historical place, but most of us walk by these buildings, walk by these spots without even knowing. So I think for us, it's interesting that you asked, you know, how did how did it make you feel? Because for us, it's always been about leaving anybody who comes on the tour with a feeling of belonging, with the feeling of the city is yours, this place is yours, you have roots here. We've had ancestors who fought for us to be here. You can be part of this.

These are stories of everyday people. So I think that was our intention going in was to leave those young folks empowered and with a sense of belonging. You know, I think there's a power to having done this for 12 years and reflect on that for sure. Yeah. Do do were you surprised by how you felt after that very first tour?

And and the reason I asked that is because I wonder if there was that same exact sense of not just, what you accomplished, but the questions it raised after that very first tour. I mean, especially as a motivator, like, even accelerating further tours. So I think for us going in, I personally was quite nervous doing it for young people because, you know, young people, they will tell you exactly what they think of you and what they think of what you're sharing. No filter. Yeah.

You you have to be authentic and truthful, and you have to share it with integrity. Right? Which is what we were doing, but you still don't know what they might be seeing that we're not seeing. Sure. But their feedback and we always do this.

You know, at the end of the tour, we'll ask people to share what their favorite story was. We've been doing that since the first day. A lot of our pedagogy around this is influenced by social justice activists and spaces that we've been part of. And hearing that feedback from them, I think, left us feeling moved and feeling like we had hit upon something. And at which point, we were only gonna do that tour.

Right? And then we were like, should we do it for the general public? And at that moment, I was like, no. The young people were great. I'm not sure about doing it for adults.

Adults have so much baggage. Will they even be open to hearing the stories like these young folks were? But I think we heard we we were affirmed a lot in the decisions that we made of what we shared, how we shared it, and the way we engage them. So, honestly, much of our tour has not changed over the 12 years Right. Except for new information or politics Yeah.

That happens, external factors. We've been able to really stay with a lot of the good things we learned when we did that first tour for young folks. And most importantly, that they left feeling something. And it wasn't just a barrage of facts, which they can look up, honestly. And so many of those young people from that first tour, they're doing the work here and now.

They're young organizers. They're folks who are doing, Palestine solidarity work. Some of the founders of the South Asian Legal Defense Fund, they were on that walking tour 12 years ago. Mhmm. And just the idea that as a young person to know that, like, yes, social moves change movements are part of our heritage Yeah.

And to see them out in the world doing their work. There's an element of youth becoming transformed and youth being galvanized by and inspired. And there's also an element of other generations, in fact, transforming themselves and seeing a different vantage point and or for that matter unwinding or unspooling some of the either history or or for that matter even, you know, kind of myths or trauma, that they've gone through as well. Absolutely. Have you had some of those moments, especially reflecting back where, yes, there are some people who've gone on to do some amazing great things, and then there's other people who report, wow, this is something that completely blew my mind about, all that I have already had to, you know, sort of learn.

Yeah. I think the 2 specific moments that come up for me, and it might be something different for you. But I think the one moment was when a friend of ours who's who's queer, who's lesbian, she was on the tour with us that day with another member of her family. And she she was already out in the community, but she said this was the first time she she in the end, when we go around and do the sharing, she shared that she's part of the LGBTQ community. Yeah.

And she said she had never felt safe to do that in a group of strangers. And I felt really honored and proud that we've been able to create that space. And the way we told the story is for somebody to be able to claim that identity. Sure. We also had another friend who shared an experience she had post 911 when she was at the gas station with her mother.

They were going to a a a dandie or a garbag because that season, you know, September and then September, October. Yeah. And she said that when she got then, just in Southern California actually, to the gas station, her mom got out and she said, no. No. Get in.

Get in. We have to leave. And that was not a story that she had shared with her partner or with her kids up to that moment. Yeah. Because, again, what you're saying, people have these traumas that they hide.

They don't know always if anybody else is going through it. But also we don't have those spaces where it's okay to share that. Yeah. So those are the 2 that really stick out for me, but there have been many moments like that. I think even for people who've been part of movements, like, when we started, we thought this would be more for the general public.

But all our friends who are activists and organizers started coming. Yeah. They started bringing their family because who can explain to their family what they do? Right. Right.

Often, you cannot, but we can. It's an instant peer group. Right. So we can do that. Yeah.

And then you can have the conversation. Yeah. But most importantly, even they needed a grounding in history because as South Asians, we often enter activist spaces and we're seen as allies. Yeah. So there is not always an understanding of the work our community has done or the specific issues that our community faces.

Part of that is because of, you know, the model minority. Anirvan can write more about that. But, we're seen as privileged across the board. We're seen as not having issues of discrimination across the board. Yeah.

And though many of our stories are about solidarity between communities, it's also specific to our community. Yeah. No. There's a there's a sharing of identities, that naturally happens. And and again, there's, you know, with great specificity comes actually a lot of universality.

And and I'm curious in in that same, you know, way of thinking about the model minority piece, why is it that the basic American or South Asian American history is you know, catches people as a secret. I mean, somebody lands so so you get off a plane. Nobody gets you with, like, an ethnic studies textbook. Right. How would you know?

Like, somebody arrives in 2010, how would you know what happened in 1910? Yeah. And I think that's been a really big challenge where maybe there's the oldest member of your community and your your friend group that you talk to. Maybe they they know something that happened, like, 10 or 20 years before. Mhmm.

And a lot of our work is actually providing a little bit more context to where we came from, what our stories have been. And sometimes that means things like, we tell stories to the other party. And the other party just being here in the bay and on the West Coast in the 19 tens. Just the idea that they were, like, freedom fighters running around and, like, no, not in South Asia. They were, like, literally here.

Yeah. And they're organizing in San Francisco and elsewhere to, like, overthrow the empire. Right. And that is part of history. Nobody tells you.

Yeah. And for a 60 year old thinking, you're not hearing the direct link to buckets saying. Exactly. Yes. So I think that's, like, a really important piece because, like, we have no plaques.

It's not in the history textbook. Your kids are not growing up hearing that in the schools. So people will come on at in our case, show it to a history event because it's one of the very few places where they can actually, like, access that history. Yeah. And the other piece of that is, for a lot of, kind of, post 1965 immigrants.

I mean, they're coming here, to some extent, as professional skilled stem workers, at least for the first wave. And there's a lot of reasons for that. I mean, the this is a post cold war context. The US needed stem workers to be able to come in. Sure.

The economy here needed it. Countries like India, for example, were over producing stem workers and, so there's always, like, push and pull factors. So it's just, like, weird founder effect where some of the first people here post 65. Something that's, like, setting up the stereotype for the whole community. Yeah.

And now with family based migration and before and after, like, it just overshadows all the different things that people do. We're so much more interesting than we think. Mhmm. But you don't know that. Yeah.

And those conversations don't exist at the, you know, kitchen table. And you have a lot of, you know, mobility, so to speak, among families. And, you know, I imagine that Berkeley, again, you you happen to do this in Berkeley, but, I'm imagining that, of course, this exact same interrogation could happen just about anywhere. Yes. In fact, it it probably should be happening more in rural America and in in other spaces where it doesn't.

You're listening to Trust Me. I Know What I'm Doing. After a quick break, let's come back to our conversation with Barnali Ghosh and Anirvan Chatterjee of the Berkeley South Asian Radical History Walking Tour. Stay tuned. Every story told is a lesson learned, and every lesson learned is a story waiting to be told.

I'm Abhay Dandekar, and I share conversations with global Indians and South Asians so everyone can say, trust me, I know what I'm doing. New episodes weekly wherever you listen to your podcast. Hi. I'm Vivek Murthy. I'm the 21st surgeon general of the United States, and you're listening to Trust Me, I Know What I'm Doing.

Hello, everyone. My name is Tam France. Hi. I'm congresswoman Pramila Jayapal. Hi.

My name is Richa Moorjani. Hi. I'm Lilly Singh, and you're listening to Trust Me. I Know What I'm Doing. You're listening to Trust Me.

I Know What I'm Doing. Let's return now to our conversation with Barnali Ghosh and Anirb=van Chatterjee of the Berkeley South Asian Radical History Walking Tour. When you both are are thinking of the work you do and and how it evolves, are are you both community historians and activists, or are you specifically South Asian community historians and activists? You're gonna get us into trouble. No.

I mean, yeah, we are we are community historians and activists. I think we are not we're not South Asian community historians just because I think there is a politics to you know, we do call it the Berkeley South Asian Radical History Walking Tour, but Anirban and I also own Berkeley history dotorg because for for decades, people have done a history of a place that's told only the history of white people. Yeah. And it's been okay to just call it the history of that place. Yeah.

So there is a power in defining the tour as South Asian because we want it, 1st and foremost, to be for our people to understand who they are. But also, we don't feel like we need we need to put ourselves in that box. Yeah. We're fine doing just South Asian history and being just community historians because of the politics of how it's been used. And we're always excited to kind of make connections.

Like, we'll talk about Indian Irish solidarity against the British Empire. Yeah. In, like, a 100 years ago, we'll talk about black and brown solidarity. It's like Mojave, Mexico. Mojave, exactly.

Bengali, Bengali, Harlem. Yeah. It's not like our like, we can't tell our stories without telling a lot about the stories along the way. Yeah. Like, we've never really connected.

Yeah. We've never been separate. Right. Yeah. And and I wonder if even that again, it's it's amazing to, in fact, reflect upon that because it can be different from the first time when you develop this to, like, the many iterations of practices that you have to go through with that too.

I'm thinking of, you know, the stories that probably catch people. Those are the ones that seem a little bit more obvious. So whether that's, you know, Kala Baghai or Kartar Singh Sarabha, you know, even Jayaprakash Narayan, the founding of Trikone, you know, dozens of others, I'm sure. When I when you think about all those sort of touch points, does the power of these stories then subsequently reside in the audiences that you have in this sort of greater South Asian American community to amplify? Or is the power in the American zeitgeist, at large to sort of recognize and integrate it better?

You know, I'm kind of asking a very zinn esque historical question, but, you know, how how do you think about that? Like, is is is the method here geared towards a specific audience? Right? Like, I mean, how do you, in a in a way, almost market this? Yeah.

I'll say from it's both. Right? I think we for me, it's both. Right. And then it also depends on the story and on the audience.

Sure. But I'll say, at least for the Kalabagay way campaign, that was a South Asian person story. So there's definitely, an aspect of representation because Berkeley is 20% Asian American, yet there are no streets or official buildings. There's some on campus that are named after an Asian American person, especially an historical Asian American person. So for us, it is about representation, but it doesn't stop there.

Because usually how cities name streets, you have to actually have lived in the city, whereas Kala's story is all about being turned away from the city. Right? So we took a lot of risk with changing the paradigm on how cities name people. You've become famous, then the city wants to name something after you. Right?

And in this case, we were asking Berkeley to reconcile a difficult history, to accept that there are people who come to our city now. We're a sanctuary city who doesn't who don't build enough housing. So it's all the history that we share is connected to the present. That affects more communities than just South Asians. Sure.

So when you are the first, you you are a symbol, but that is never our goal to just remain a symbol. And as part of the campaign, we brought together many different kinds of folks as well. So our stories can be relevant to folks who are not just part of our community. So that's when we are becoming part of the bigger narrative Yeah. And understanding how it specifically might affect South Asians.

But in many cases, other people can connect to color story for different reasons. Like, we worked with indigenous folks. We worked with other Asian American communities, with housing activists. It's not like just South Asians or Asian American folks have to fight for the street name. Also, the location of the name, it's right in downtown Berkeley.

Yeah. Many times when you have street names like this, you know, it you're excluded into a Chinatown. You've made it a place for your community. Right. We'll give you a street name.

Yeah. There might be a street leading to the Gurdwara that's called Gurdwara Way. But to just have it be a normal part of your city where people are, hey. We should pedestrianize Kalabagay Way. It's just regular part of the conversation.

Yeah. People walk by it all the time. It's near the BART station. I think that's the aspect of integrating it into the American fabric Yeah. And not just how it affects South Asians.

But, of course, being in seen as integrated into the American fabric while maintaining your identity and history, that has power. And I think for too long, folks who came before us, that was a struggle, for them for many reasons. You wanna add something to that? Yeah. One of the parts of the Call of a Galloway campaign that really And for them, just that clear connection between we need to make space in the city for newcomers and being able to name a downtown street after somebody who's turned away from the city.

Right. It's a direct one to one thing. It's, like, it's not, like, pro housing way, but, like, it's using a real person story. And I think that's kind of the point where we wanna be specific around, like, yes, we tell Calabagay's story, but it's part of a much larger narrative. And it shouldn't be limited only to our community.

I wonder if that specificity of empower of that very individual story requires coalition building at some point to, you know, kind of penetrate into the narratives that are out there. And also for that matter for it to, have some kind of longevity as well. Because if it was specifically, you know, again, like, Gurdwara Way or something like that, then, you know, it sort of is there's a cul de sac there literally and figuratively that, you know, can't go anywhere. And and in that coalition building that you both are building, I I definitely want to ask particularly, Baraneli, this has this kind of thread of activism, and the idea that you have power that goes beyond yourself, and you can be both specific and build coalitions. Has that always been kind of baked into your temperament, your, your general nature, and and especially now as you're running for public office.

Right? I mean, is there is did you need to practice this first before sort of crossing a precipice to, you know, creating a tour, running for office, things like that? I'll say for me, it was very clear to me that it needed to be a coalition. But also, you know, as we share these stories and the stories transform people, they also transform you. Right.

Of course. So you also learn from the things you're telling people that these people did Yeah. And what kind of organizing and activism feels effective. What feels the right way to approach an issue like this. So when we were gonna do this, of course, it was gonna be through coalition building because both of us, you know, know the the the problems with it just being bad representation.

That only takes you so far. And this is something we've talked about. This is something we talked about on the tour. But I think I have also been doing work in the city for a long time. I've been on the transportation commission for 10 years.

I'm the vice chair of the planning commission. I also understand the process of how things get done and how decisions get made. Yeah. This is not always something that folks in our community, especially activists folks, are wanting to be on the other side of. Like, you're not often wanting to be at the table because it's it's a it's a hard place.

Yeah. Yeah. It's it's much nicer to be on the other side and, you know, not nicer. Not nicer. You know, it feels better.

Yeah. Did you grow up that way as well? Like, they were was this a transformation that you felt particularly in immigrating? Yeah. I mean, definitely a transformation.

Yeah. But I think what the reason I craved it and hungered for it is because I didn't find a sense of belonging when I moved to the city of Berkeley. I had an expectation that I was coming to this place, that was a home of the free speech movement, that was progressive, and yet I went to some as a landscape architect, went to many community meetings all over California where people would say you had to have lived here a certain number of years for you to have an opinion. As if our journey as an immigrant, our experience in our homelands has no no impact on what we bring and what we contribute. Relatively discounted.

Right. So so I think that really sort of made me angry. Yeah. And also, I felt like if I had to belong here, and belonging is such a powerful tool. That's the only way I think you can change a place.

You have to feel like you are invested in the well-being of a place. Right? And if that's your home, how do you do that if everybody else around you is making you feel like you don't belong? Yeah. Right?

Yeah. So I think I took that to heart that if nobody else was gonna do this, then I was gonna have to do it for myself. And so for me, this power of belonging through doing the tour in Kalabaghay way, it's selfish. It's very personal. Right.

That's what's empowered me to run for office. Mhmm. Having gone through that experience. And, hopefully, other people there are other people who don't need that who are totally fine. But I needed that, and I think I meet a lot of people on the walking tour who also need that.

And if you're gonna be running for something in a place that is not primarily South Asian, you wouldn't have to build those coalitions. You have to be aware of the issues that people in other communities are facing. What it does is attunes you to looking for the leaders and the people in those communities Yeah. And what those issues are. You are more attuned to that because you know what it's like for your community.

Right. Your lens is perhaps looking for that in different ways and your experiences have now, almost kind of curated it, so that you can your your walking tour, is activism in life, so to speak. Right? Let me ask a slightly different question for activism in a slightly different way where it's not necessarily public office, but it's a lot of interrogation of intersections. And and for you, Irvin, you've explored and done some really, I mean, just amazing interrogation, particularly of the intersection of black America and the South Asian American or even the Indian American experience.

And, of course, right now, the most visible embodiment of that is vice president Harris. And I know that some of this comes up on the tour, especially as well. But in examining this, what lesson should Americans take away from this very, very deep and complex Mhmm. Relationship that goes well beyond what the surface story is of vice president Harris and even MLK and Gandhi and all that. But if one were to explore and interrogate it to the degree that you have, what are some of the lessons that they particularly should take away from the lens of representation and activism?

A lot of times when people come to the US, and this is something, Bernadette, that you talk about growing up in India when you looked at, like, American movies that made their way to India. It's like the US is like it's a white country. Like, when somebody says, oh, like, I'm you know, something or the other with the Americans. Like, we know exactly which Americans. Right.

And That's like 65. Yeah. Yeah. I mean, we chuckle with that, and yet, like, the truth is is that that's exactly right. And it's definitely, you know, impressions from afar are very much baked in to people's narratives, either when they arrive or, for that matter, even passed along, to the next generations.

And nobody tells you when you arrive that white America didn't want us when we were here. Just the idea that pre 1923, where citizenship was so tenuous, it's 1923, and every single Indian American, you no matter whether, like, you can go and argue to people, you can argue to a judge that I'm kind of white, I'm honorary white, look at my cast, look at my Indo European languages. Yeah. They don't care. And certain local judges gave people citizenship.

But then in 1923, Bhagat Singh Thind case, the Supreme Court was, like, no. We don't believe you. You're not white. You are literally not white. An entire ethnic group was stripped of our citizenship.

And it was the first time in American history that there was this, like, mass denaturalization of an entire ethnic group. And nobody tells you that the day you get off a plane. That, aspiration to whiteness, that that is so tenuous. And maybe that's not the best strategy to become American. And it changed.

I mean, we in 1946, up to a 100 people from, let's say, India were allowed to become US citizens per year or to come with the kind of that intent. And in 1965, it all changed. And what was happening in the 19 sixties, I mean, it's all the movements. And there's a couple of different reasons why the 1965 immigration laws changed everything for us. There was it was a cold war context and the US needed more STEM workers.

So that's the reason economically, why they needed more people from South Asia. Because it's a cold war, the US was also trying to basically trying to front and front of, like, all these third world nations saying, like, are you gonna go with Soviet Union or are you gonna go with us? Yeah. And just literally, like, we're not gonna allow your people, telling people from, like, Indonesia and India and all and Egypt and all these other countries, you're not even allowed to come to our country and get citizenship. This is what we think of you.

That was an issue. Mhmm. And when folks in Pakistan and India and Indonesia, these countries are looking at the US, they're seeing the way that black activists were fighting for any kind of basic civil rights equality, and they're, like, yeah. We don't believe you. I mean, at least the Soviet Union isn't fronting that way.

Yeah. And the US was, like, this is embarrassing. You know, cold war context, like, the news coming out of the US is embarrassing. And, finally, little by little, black activists were overthrowing some of the most racist laws in the US. I mean, getting getting the civil rights act, the voting rights act, and the 1965 immigration reforms.

Well, that wasn't the primary goal of black activism of the sixties. It happened in that context. Mhmm. And I don't think South Asian America would exist if it weren't for the really critical role that black activism played in winning civil rights for everybody, including us. And, secondarily, like, winning immigration rights for everybody.

And citizenship wasn't granted to us. Like, there's this idea that we live in the Bay, we live near Silicon Valley. There's this idea that we are, like, we're awesome. We're so blessed. We like, the US should be lucky to have us.

And, yes, absolutely, they should be lucky to have us. Yeah. But nobody saw that until the right for us to even be here was 1. As a data scientist, a couple of years ago, I was looking at the 1940 US Census Mhmm. And, I got this dataset, and I was trying to figure out, like, what was happening with South Asians in the US.

And they didn't always, like, list people's birthplaces, but I then I was, like, okay. Well, let me look at, like, really common last names, like Khan or Singh. Mhmm. And so I looked specifically at Singh because they there were a lot of, sick folks here at the time, relatively speaking, huge proportion of the community. California.

Yeah. So, I took the entire US census data set. I pulled out every single person with the last name of Singh, and their average age was, like, in their forties. And I'm look like, late forties. And I'm, like, how is it that, like, immigrants are, on average, in the late forties?

You think they'd be in their twenties thirties. And so this is like a data thing. Like, I'm sitting there with, like, Excel and JSON files and all that. And I'm doing my digital humanities work, but suddenly it's like, oh, they didn't allow us to be here. Yeah.

So there's this group of aging single men who are here. And until and there are aging in place, they there are no women here. Right? And it's it's heartbreaking. And seeing that data, and then suddenly black activists in the sixties open up the floodgates for us.

If we knew that, I think we would we would walk through race a little bit differently. We would look at moments like Black Lives Matter a little bit differently. We would look at the story of Kamala Harris a little bit differently Mhmm. Of just knowing how important that is and the stories that are kind of behind for a lot of people to just kind of appeared out of nowhere. Maybe not so much in the Bay Yeah.

But with context. And with that, you know, you you weave this story with data and thinking about the questions that it brings up. And now when you think about that narrative from the forties, connect the dots to the sixties, think about all the different movements that have trans that have both transcended and transpired since then. And now in 2024, where we have people that are marginalized that people should be asking, related back to this kind of complexity that that you talk about? And that goes beyond just the, like, hey, she's someone who represents both of these, you know, sort of segments of society, because that's the that's the baseline and that's the easy way to explore that.

Yeah. But, you know, there's a second, there's a third, there's a fourth question that perhaps should be asked. Yeah. I think I'll say personally, I've been very excited Yeah. For VP Harris.

And part of it is seeing somebody who is biracial. Yeah. You know, there are so many other things to be excited about. Sure. I think, you know, the fact that it's a biracial person, that also complicates identity and representation by itself.

I think from a historical perspective, it would be impressive if we, as South Asians, were able to confront the the anti black Yeah. Blackness that we have in our community. Sure. Maybe this is that moment. Right?

Historically, we have been anti black, though I think Black DC Secret History is a great example. The stories that Anirban has documented there of how you don't have to be. But we have had folks in the past who have seen each other, seen the struggles of of South Asians and black communities, being able to see each other in our struggles. We are not separate. One struggle isn't necessarily bigger than the other.

That's how people have come together by seeing the commonalities. Solidarity is is powerful. So that's my expectation of this moment as a South Asian person talking to South Asians. Hey. This is a great time Right.

Not just to show support for for, BB Harris, but also look around in your own community and see what is happening with black folks in your community, around policing, around poverty, around housing, around leadership. Yeah. This is this is our opportunity to do better. I I love that that concept of excitement generating, movements, but at the same time, really kind of peaking interest in the extra extra interrogation and with self reflection for that matter, both as individuals and as community.

You're listening to Trust Me.

I Know What I'm Doing. After a quick break, we'll come back to our conversation with Barnali Ghosh and Anirvan Chatterjee of the Berkeley South Asian Radical History Walking Tour. Stay tuned. Conversation. It's the antidote to apathy and the catalyst for relationships.

I'm Abhay Dandekar, and I share conversations with global Indians and South Asians so everyone can say, trust me, I know what I'm doing. New episodes we so everyone can say, trust me. I know what I'm doing. New episodes weekly wherever you listen to your podcast. Hi.

This is. And you're listening to Trust Me. I know what I'm doing. Hi. This is Madhuri Dixit.

Hi. This is Farhan Akhtar. Hi. I'm music recording artist, Sid Sriram. Hi.

I'm Krish Ashok, author of Masala Lab, The Science of Indian Cooking, and you're listening to Trust Me, I Know What I'm Doing. Hi there. I'm Abhay Dandekar, and you're listening to Trust Me, I Know What I'm Doing. Let's rejoin our conversation now with Barnali Ghosh and Anirvan Chatterjee of the Berkeley South Asian Radical History Walking Tour. I'm curious for you both, like, you know, we're we're talking about this and there's a lot of enthusiasm and excitement, but it has to also, you know, feel for you both a little bit, you know, like a, you know, kind of a self reflection, journey as well.

And are there things that either of you had to perhaps unlearn about yourselves dramatically in curating the walking tour? Or for that matter, not just curating the walking tour, but really sustaining walking tour or, for that matter, not just curating the walking tour, but really sustaining this activism and so that it stays within your DNA and it just doesn't sort of fade and and sort of dampen with time. Right. I think our first story that we do, Anirvan, if you wanna talk about that a little bit, is been a story that I think we wrote to to keep us inspired. Right.

So I don't know if you wanna talk about it a little bit. Yeah. So the first story, we, tell on the tour, it's a story of, Tinku Aleishtiak, who is a somebody from Berkeley, a gay, Bangladeshi, American activist, and just also, like, a just really wonderful person and friend. And he is somebody who moved here, studied computer science, got involved in early, like, 19 eighties gay activism, was one of the early founders of Tricone, got involved with a group called Queers Undermining Israeli Terrorism, doing, work in Central America, like a lot of people in Berkeley did Yeah. In the 19 eighties.

Doing homeland Doing a lot of homeland activism and doing a lot of US activism, and he is somebody who went back home to take care of his mother. He is somebody who has navigated, doing work with other immigrant Bangladeshis to send money home. And really, like, a three-dimensional figure Yeah. As like, when I look at Dinko, I look at somebody who's, like, had economic stability and found love and done really critical justice work, has been a caregiver. And we're really proud and to be able to share stories of, like, rounded, three-dimensional, complicated South Asians where it's not like the activists are over here and the techies are over there Yeah.

Or the caregivers are over here. We can't Or our queer folks only work on queer issues. Right. I think that's something that is definitely I think, Anirvan, you have for a decade now said that you wanna be Tinku when you grow up. Yeah.

And I think for me too, it gives us this sort of, permission to be our whole selves. Yeah. And I think a lot of young people and even older folks And by the way, is that something that you you truly had to, in in a way, create space for yourself? I think so. And that's that's Absolutely.

Because, you know, we are all, I think when we think of activism, most people think of protest. Right? It's the most visible form of activism. Sure. I do not like going to protest.

I've always been a little bit of an introvert. Yeah. I'm very sensitive to sun and to crowds. One of the reasons I enjoy living Right. In the US is because it's not India where you know?

So for me, going to a protest was a huge, it took a lot of, like, physical and emotional strength to do that, and I did it. And I had Anirban's company in doing that and a cohort that I went to it. So I'm able to advise people that if you wanna go to a protest and you're not comfortable, this is how you have to do it. Yeah. But it's a huge leap for me, but I thought that was the only way.

And as we've done this tour, a big part of what we do on the tour is in each story, people are doing different things. People are being murdered by the British. Yeah. But people are also, like, all of a guy doing community building, like the youth at Berkeley High, you know, doing teachings. Like, there's other people are writing.

Yeah. There's so many ways to be part of change. Right. And I also thought that the only way to be part of change is to actually be out on the street. And you realize that even those people out on the street, like our friend, Deepa's book about the social change ecosystem talks about all these roles.

And we are guilty as organizers of uplifting some roles and not Sure. Looking at the folks maybe or from the back. Right? I mean, there's always the photo in the newspaper of the person holding the bullhorn or with their fist up in the air. Right.

And, yes, and there's, like, a 100 people behind them to make that work. Right. From people cooking to people doing policy work. Yeah. I could but you need that striking image, but that's not enough.

But we do see a lot of young people struggle to be part of social change while they also are trying to find a job. They're like, are we allowed to work in capitalism Yeah. While fighting for change? And I think Tinku's story just shows us most of us will probably be lucky to have a lifetime to make change, and you don't have to rush it. Yeah.

You can you can Let it let it marinate. Let it marinate. Let it mar sometimes it's good to take a step back. Sometimes you have to push yourself because that's the moment where you have to step up. Understanding that is critical.

I love how you use the word sort of like this wonderful three d first. Right? That, like, things are they don't always have to be in 2 separate lanes. You can, you know, you can live in 2 or 3 or 4 or 5, you know, different lanes. And on top of that, I think what you're both speaking to is the comfort of your own discomforts.

Right? And really being at peace with that. I'll get you both out of here on this. You know, for for those people who are kind of learning about your work for the very first time now, how do you hope they feel after they experience the walking tour or even see some of your work online or have been exploring this slice of activism? Like, what do you hope are their very first, sort of thoughts when they sort of experience your work for the first time?

Do you Yeah. I mean, organizing happens in organizations, and there's a certain thing that a lot of, folks in countering activism for the first time. There there's there's this fear of, like, I need to do it by myself. I need to amend this for myself. I just people just get stuck.

And, really, a lot of our work is, like, yeah, this is normal. Like, a lot of us have been doing this for generations. Every story we tell is in some way about the collective. It's about people who are learning and doing it together. And, really, we wanna make this feel really approachable.

Mhmm. Social change movements are not, like, one by heroes. It's one by a lot of people pushing a little bit in a certain direction. Yeah. And if you can kinda just get that across, if we have 30 or 40 or 50 people come on the walking tour and somebody walks into a meeting a week later or a month later, mission accomplished.

Yeah. I think for me, it's also that people, like I was talking about before, feel a certain kind of rootedness and belonging. Yeah. That this is not just something they're doing for others, which is which is great to be an ally, but that our own communities benefit from it as well, that we have our specific issues, and also that we understand the complexity of our own communities when it comes to class and cast. Right?

So if you come on the tour, you will walk away not just feeling pride, but it's not just again about pride because so many of the stories are about challenges that we face from our own community members. When Tinku was outed, it was within the Bangladeshi community. We talk about labor trafficking that's happening within the South Asian community, the Indian community. That brings up issues of cast. Right?

So, again, it is to give you a new lens and a new perspective to look at every situation, to also not have a reaction that is a knee jerk reaction, to be thoughtful and nuanced, to look for the leaders and the voices that are missing in who's telling you the story. So to develop an intelligence around how social change happens. And I think lastly, to figure out today what your role is gonna be in that. Right. Because, like, it honestly, social change doesn't happen just by a few people.

It it lasting social change doesn't happen that way. Yeah. You can you can have some things change, but lasting social change only happens if you're able to ultimately change everybody's point of view. Right? And that takes hard work, and that takes that conversation with neighbors, with families.

Right. And there are organizers who are creating those resources. I think there was a letter for black lives that was translated into so many languages. Right? There is so much power in the tools that we have, in the Marathi that you know, to be able to talk to so many members of our community who, honestly, we also leave out of these conversations.

Much of the story is about using language tools, using Punjabi and Urdu to talk about Right. The anti colonial movement, to talk about reaching out to people in suburban areas and in rural areas, not just speaking to people in urban areas. There are so many lessons that we share on this that we hope we hope we leave people with the whole toolkit of ideas and ways to get involved, and the only thing we ask is get involved in something. One thing we didn't touch upon that I would like to end with is we started the tour primarily at that point because we wanted more South Asians to be engaged in climate activism. This is something that affects people here, but also in our homeland.

And it's one of those rare issues that if you can work on reducing emissions here, it has a direct imp like, no other issue has that kind of direct scientific impact. Correct. So our goal was as South Asians here, living in a country that has historically one of the highest emissions, while seeing folks in India, in Bangladesh, and Pakistan, and in Nepal suffer right now and for decades now, these direct impacts. We have a lot of power. The way we vote, what you know, how we choose to live to some extent, but also how we behave.

The way we behave and what policies we support. Yeah. I mean, that's one of the reasons I'm running for a public transit office. Yeah. It's because I see that as a next step in my role fighting climate change.

But that's how we started. Of course, since then, we're like, yes, but also Right. There's so many movements. Pick something. But that was our goal.

So it's always been grounded in that idea of we need to be active in in these issues that affect us and everybody else. Well, whether it's the connectivity of climate change, whether it's heroes at the forefront, or whether it's gathering and creating a sense of belonging. You both are doing such tremendous work, and I know that people are really galvanizing around it, being inspired for sure. Barnali and Anirvan, thank you so much for for joining me today. What a treat, and wishing you all the best for all the continued work that you're doing.

Thank you so much. Thanks so much, Barnali and Anirvan. And in 2025, please look for touring dates in both Berkeley and also in San Francisco's Mission District. Information is available in the show notes, so please check that out. Photography shout out now to the Bay Area's own George Nixon, a true pro.

The days are getting shorter, but that shouldn't stop us from being kind and being the light for someone in need. Till next time, I'm Abhay Dandekar.