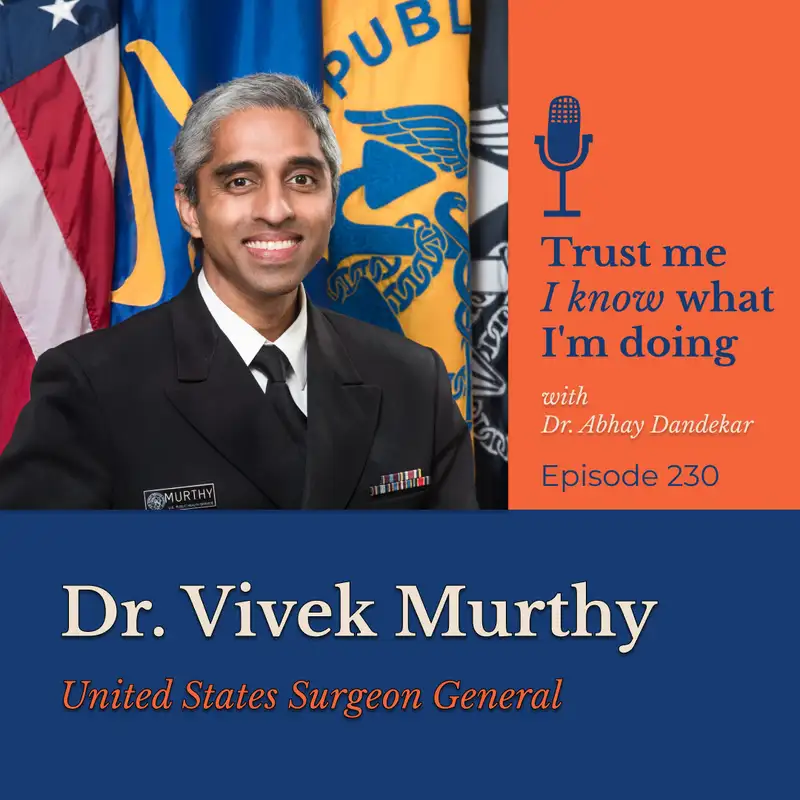

Dr. Vivek Murthy... on human connection, community, and optimism

Download MP3Hi. I'm Vivek Murthy. I'm the 21st surgeon general of the United States, and you're listening to Trust Me. I Know What I'm Doing. Yeah.

My name is Abhay Dandekar, and I share conversations with talented and interesting individuals linked to the global Indian and South Asian community. It's informal and informative, adding insights to our evolving cultural expressions, where each person can proudly say trust me, I know what I'm doing. Hi, everyone. On this episode of Trust Me, I Know What I'm Doing, we share a conversation with doctor Vivek Murthy, United States surgeon general. Stay tuned.

So in the spirit of Thanksgiving, I hope that listening or watching is a meaningful part of your day and serves as an additive supplement to building deep connections. I know it's a tall order to take the time and effort, and so I'm grateful to you for engaging with me on Trust Me, I Know What I'm Doing and for sharing this with your friends and family. And, of course, if you're enjoying these, please take a moment and share a kind rating and maybe a written review wherever you're experiencing this right now. I sincerely appreciate it. 2024 has been an interesting year for Americans, and especially as a pediatrician, I'm so proud to care for children and their families every day because like sharing conversations with you as a listener, caring for patients brings me the joy of cultivating trust through deep relationship building.

It's not an easy task though to keep a population healthy. And as hard as it is to ward off disease and promote wellness, it's perhaps equally as hard to combat disinformation, combat the ills of social media and gun violence, and combat perhaps the greatest threat to our modern existence, loneliness. Connecting people and connecting health by weaving our own story into the stories we hear from others every day is what fuels us, and so it was such an honor to share a conversation with the United States surgeon general, Doctor Vivek Murthy. Vivek was raised in Miami, Florida after his parents had immigrated from India via Britain and Canada. After his education at Harvard and Yale and experiences as a doctor in caring for patients and educating hundreds of students and residents, it was some of Vivek's galvanizing work that sharpened many eyes on his talent to rally attention around public health, scientific research, and prevention, especially with his leadership to help train women in rural India as community health workers, build networks of collaboration to improve efficiencies in clinical trials, and organize doctors across the United States to advance accessible and affordable care.

He first served as surgeon general under President Obama and briefly under President Trump, and then again, now currently under President Biden. Doctor Murthy has been spearheading many critical efforts, laying the foundation for a healthier country. And even while tackling pandemics or the threat of Ebola, recognizing addiction as a chronic illness and not a character flaw, or concentrating on the mental health stressors of youth or young parents, his journey continues to be informed by his family background and the core principle of finding health and joy in human connection. So when we caught up recently, it felt natural to talk about things like parenting and the imperatives of doctoring and promoting health through connection and even mangoes and our own Indian background. But I really wanted to first know, in an ocean of health obstacles facing our country and our planet, how he prioritizes and focuses his work.

It's hard. It's one of the hardest things that, I have to do in this job is figure out what we're gonna work on in a universe where there's so many pressing health needs. Yeah. And so one of the things that, you know, I learned the first time around when I served as surgeon general was that, you can't do everything, and you have to make choices. And so here's how I think about the choices that we make.

I first try to understand, like, what are the big public health issues facing our country? Start with that broad set. Second, I try to understand what is on people's minds out there in the public, the people we are trying to serve. Sometimes, the issues that they deeply care about or worried about may not necessarily be at the top of our list in terms of, you know, public health experts and doctors and nurses and others in terms of what they're thinking about. So I try to understand what do people in the general population what do they need?

What are they concerned about? And then try to look at the universe of what is being done more broadly on these issues then, in the broader medical and public health universe. And sometimes I find areas where there is an need that's urgent that people widely feel, but that isn't actually being worked on, by many people or it's it's sort of silly. It doesn't have as much momentum, you know, in the public health space. And then I'll think about where our office is, you know, can really serve well.

So for example, if there's an issue that needs, a lot of basic science research, that's critical. That's important. Our office is not equipped to do basic science research. We don't fund it. We don't, you know, conduct it ourselves.

Right. So I'll look at the areas where it's it's where our office can actually make a difference by bringing research data together and sharing with the public by helping raise awareness about a critical issue by convening, the powers it be to actually take on a critical issue, moving an issue forward in public conversation, so that action can be taken. So I'll put all of these factors together and then ultimately try to make decisions with my team about what issues we take on. And it has actually been that experience, our process, that has led us to focus, initially on COVID, which we did. We came into office in the the throes of the COVID 19 pandemic in 2021.

But it's also then led us to work on issues like mental health, like loneliness, like burnout among health care workers, and like the issue of social media and its impact on kids. I I I love that mechanism and and sort of method of problem solving. I I'm in hearing that, I almost feel like we all need a Vivek Murthy app to sort of, like, plug in our our variables and come out with some great architecture to how we solve problems. You know, you you've traveled extensively domestically and internationally, and and you've spoken so so elegantly about the importance of curating those human connections and really building and strengthening and maintaining and sustaining them. For those who are embarking on that connection journey, and they almost feel like they have to be, to some degree, an extrovert to to jump start or even rekindle some of those relationships.

How do you approach meeting new people and appreciating in a way both the the peace and power, of those connections and and particularly for thinking about coaching people through that, especially those who may feel that they're anxious about the next human connection being either a home run or or something very clunky and awkward? Well, that's such a timely question because I do think there are many people who are struggling with social anxiety right now, and they're feeling a sense of disconnection. I'm quite sure how to bridge that gap and build a connected life they want. The first thing I would just say is is to recognize that a lot of people are right now are struggling with that sense of disconnection and loneliness. So if you're out there and that's how you're feeling, you're not the only one.

Yeah. But second, also to realize that every conversation you have doesn't have to turn into a best friendship, you know, or into a romantic relationship. It doesn't have to be everything to you. In fact, I think sometimes we put too much pressure on some of our relationships to be everything to us. Instead, I think what's important is to to recognize that every interaction we have can serve a different purpose, like in our life.

Some can make us feel good just for a moment. That might be a momentary smile that you exchange with somebody on the bus, you know, or maybe a moment of gratification that lasts for a few minutes. Right? You see somebody in the grocery store who maybe spilled all their apples onto the floor, and you pause and you help them pick it up. Or maybe they do the same thing for you, or maybe you're in a rush and they let you, stand in front of them in line because they know that you've gotta get get out of there quickly.

Yeah. These are just momentary interactions where they leave us actually feeling better. And then there are the conversations we have with work colleagues, with people who turn out to be friends or to some case to be our best friends, and those can take time to develop. But I also just wanna say in terms of being an introvert or being an extrovert, I know this is on people's minds sort of how to navigate as an introvert through the this world we're living in and how to manage loneliness because we live actually in a world that's very extroverted. And what I mean by that is that the culture in our world often tells us that to be doing it right, meaning to be socializing right, means we have to be living an extroverted life, going to big parties, going out all the time, being with large groups of people.

But that's not how everyone operates. Right? And I say that as an introvert myself. Sure. I realized that, for me, I to I I the introverts and extroverts both love being with people to some extent.

They need human interaction. Where they differ isn't how much human interaction they need and what form it takes. So introverts tend to need more time to themselves, to rest and recover and recuperate, reflect. They also tend to prefer interacting with people in smaller groups, sometimes 1 on 1 as opposed to, like, large groups and large parties. And so if you if that's who you are, that's okay.

You know, that's the and for me, like, that's meant that I just spend more time 1 on 1 with people having conversations. I'll call up a friend to catch up 1 on 1. I'll have dinner with 1 person or 2 people. Like, when I go out, I don't go out to that many parties per se, but I feel like I've been able to enrich my life in human connection in in smaller doses, if you will. And that's worked out really well for me.

So these are just a few things I I try to keep in mind. And finally, just this. This is to recognize in the vain spirit of not putting too much pressure, you know, on your interactions is just to realize that a little bit of time, a little bit of being present can go a long way to helping us feel connected. So if you have, let's say, 5 minutes on the way to work and you pick up the phone and you just call an old friend and just say, hey, I'm just on my way to work. I had a few minutes and I don't know.

I was just thinking about you. Just wanted to see how you're doing. That might be 5 minutes worth of a phone call that you make, but it will leave you feeling good for a long time. Similarly, you see if a coworker is struggling at work or a classmate who's having a hard time just sitting next to them in the dining hall or the cafeteria or swinging by their office at the end of the day just to say, hey. I just wanted to check on you and see how you're doing and having a 2 minute conversation.

These are the kind of interactions that remind us that we're not actually alone, that we're part of a broader social fabric, if you will, and that other people are often just as hungry for human connection as we are. It's so interesting you mentioned that because with that framework, in that time is not dependent, on this. And even sort of the energy that's expended, it could be a moment, it could be, you know, an hour, but really relishing that and taking advantage of it. And yet I I wonder often whether we also need to pay attention to the expectations behind that because, you know, systems need to be in place for that. If I reach out to a friend for, you know, a few moments even on my drive home and and I wanna, just catch up briefly, I was thinking about you.

I hope that the expectation is okay that, yes, it's okay for us to just have a 2 minute conversation. I I was thinking about my I dropped my son off to college and, you know, they don't have dining halls the same way that that that we used to, that there are a lot less of those kinds of gathering. So or gathering spaces. And so I hope the expectations of individuals and systems somehow sort of get allow us and give us better licensure to, to appreciate some of the things that you're talking about. I think on that point, Amay, sometimes we sometimes we have to be just a little explicit, you know, with our friends about that.

You know? Like, for example, you can imagine starting a conversation with a friend saying, hey, I I I was thinking of you. I wanted to call and talk to you. You know, I I'm I'm just have 5 minutes here because I'm I'm almost at work. But I've been thinking about you for a while.

I keep putting off calling you for thinking that I I wanted to talk to you for an hour, and I would love to, but I didn't wanna let another day go by, you know, without just at least saying hello for 5 minutes. And is that okay? And I guarantee if you approach it that way, most people will be really happy. But, yeah, of course, I understand. I know.

Because most people are in the same boat where they also have a list of people that they think at some point, I wanna catch up with this person, but that time often never comes because we're waiting for an hour or 2 hours to just be able to be on the phone or hang out with somebody over dinner. But it's in these small moments that, that glue of human connection really forms, and so that can make all the difference. Totally. I I I you know, we're both parents, and we're likely of the same generation of of adults. And and we certainly live in an era where there's a lot of questioning and, in fact, some deep trust issues of our own instincts and how we seek validation and the prospect of succumbing around almost every corner to comparison with with other parents, with other children, with other entities.

I I'm curious how you've been able to sort of connect the dots then between building those human connections as you just mentioned and mitigating the stress and anxiety that that many parents feel very palpably these days. And are there particular observations and and tips and tricks that that you've really encountered that are very additive and and restorative to bringing instinct and connection back to parenting? Yeah. I really feel for parents today because I think that the amount of stress and expectation that sits on parent shoulders is really quite astounding, and I think it's taking a toll on the mental health of of parents everywhere. And we know that the mental health of parents impacts the mental health of kids at the end end and vice versa.

And so I do think, you know, it's I think many people are aware now in our office for the last few years and working on the fact that we're living in the middle of a youth mental health crisis. But a key part to addressing that is supporting parents as well and their mental health. Now one of the things that has worried me about parents in particular is that they are struggling with levels of loneliness that are actually higher than the average population. So about 65% of parents are struggling with loneliness. If you look at single parents, by the way, that number goes up to 77%.

Sure. And this might seem very obvious to parents. But the people who are not parents, they might be surprised thinking that, oh, well, if you're a parent, you've got kids in your life, you got people in your life, how could you be lonely? Right. But for many parents, like, the things that they're struggling with are not just hard, but they become even harder, when you feel like you can't share those struggles with other people and you're dealing with all this on your own.

Now this sense of shame that many parents are carrying with them and not being able to do every single thing that they think they're supposed to do for their child, I think has really reached a a breaking point. And I think it is happening in part because the expectations on parents are being dramatically ratcheted up in this culture of comparison, that has developed, you know, especially in recent years. Some people have been comparing themselves to each other for millennia. Like, that's not new. What is new is this scale at which it's happening.

And, you know, if if you're a parent out there, you you go online, you you check your social media account, and you're getting this constant stream of messages that are telling you exactly what your kid should be eating, how they should be sleeping, how should we sleep training them, how what how many activities they should be involved in. And you're seeing all of these pictures of how to raise your child that may be different from how you're raising your child. And the whole time you're thinking, gosh, should I be doing that? Should I be doing that? Should I be doing that?

And you look around you, and it seems like all the other parents have a lot of this stuff figured out. Right? The classic example of this that I encounter when I travel around the country and talk to parents is around how to manage technology in your child's life, right, which is a universal struggle now among parents, particularly with social media. How do you manage your social your kid's social media, practices and experiences? And from the outside though, interestingly, I was surprised to find that parents aren't talking about this with other parents as much as I thought they would be.

And I think part of the reason, and we see this even in our own life, my wife and I, is I think parents look around and they figure people other people aren't talking about it. They probably figured it out. I'm the only one who hasn't been able to figure it out. I need to figure out how to be a better parent. Oh my gosh.

You know, how do I do better? And so Right. Struggles in life are not of are of not entirely avoidable. We don't wanna we we can't eliminate struggle. But when you struggle alone, that makes it dramatically more stressful, and that's what so many parents are dealing with.

That's why I strongly recommend that that parents actually start talking to one another about some of these challenges they're dealing with with parenting, whether it's the challenge of how to manage social media, the challenge of how to manage the many extracurriculars that parents feel pressured to engage your kid in. Even the challenge of just knowing how to manage mental health conditions and that your kid may be dealing with their behavioral challenges. These are much more universal than we think when we talk about it with each other as parents. We're more able to help each other. We're also just more able to realize that, hey.

We're not alone in these struggles. I wonder in thinking about that if there's lots of opportunity there to kind of capture, at least for our generation, the nostalgia of building those relationships. And like you said, comparison is is not something that is that is brand new, but in at least thinking about conversations as sort of an antidote to at least learning a little bit more and not necessarily having that social media doom that that often accompanies feeling isolated and alone in that parenting journey.

You're listening to Trust Me, I Know What I'm Doing. After a quick break, we'll come back to our conversation with Doctor Vivek Murthy, United States Surgeon General.

Stay tuned. Conversation. It's the antidote to apathy and the catalyst for relationships. I'm Abhay Dandekar, and I share conversations with global Indians and South Asians. So everyone can say, trust me.

I know what I'm doing. New episodes weekly wherever you listen to your podcast. Hi, everyone. This is Vikas Khanna. I am a chef.

I am an author, filmmaker, documentarian, and you're listening to trust me. I know what I'm doing. Hello, everyone. My name is Tan France. Hi.

I'm Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal. Hi. My name is Richa Moorjani. Hi. I'm Neil Katyal, and you are listening to Trust Me, I Know What I'm Doing.

Welcome back to Trust Me, I Know What I'm Doing. Let's rejoin our conversation now with United States Surgeon General Vivek Murthy.

I I know one of the real anxieties that, many of us have, as parents is the sort of threat of, of course, gun violence. And I'm so grateful for all of your work in calling this out and and declaring it a public health emergency in a way, and yet many of us feel helpless and hopeless, in being able to, in fact, make any progress towards making environment safe and, you know, communities safe for that matter. So I'm I'm curious, of course, absent of the political part of this, But but do you have thoughts on the sort of what and how people can act individually?

How can they, you know, educate themselves and and empower themselves a bit to ensure that these communities, are safe or their environments are safe enough so that they can feel a little bit less anxious and and secure. In in essence, it boils down to, you know, what can we do? Yeah. Well, I let's just if you step back from a moment, you look at some of these big stressors that parents are dealing with. You mentioned, that violence, safety, gun violence in particular, is an important driver.

I hear this from parents a lot. And now we have the majority of kids and parents are worried about a shooting taking place in their in their school, and that's a terrible position for a parent and child to have to live with each day. But we also know that the mental health crisis among kids has become a huge source of stress among parents. We know that managing social media has become very stressful for parents, and we know that the loneliness and isolation that parents are dealing with has made all of this worse. These are just some of the stressors.

The other thing that we know, by the way, is if you look at time and how parents are spending their time, here's something that surprised me. Parents, and this is the unsurprising part, are actually spending more time working today than they were a few decades ago. This is moms and dads. Yeah. That's not that surprising.

Okay. I think many of us probably would intuit that. Right. Here's the part that is surprising. Both moms and dads are also spending more time with their children than they were a few decades ago.

So if moms and dads are working more and spending more time in childcare, The question is where is that time coming from, that extra time? And a lot of that time is coming from, you know, activities that would help a parent rest and recuperate and build relationships. Right? Those three things are really important. And so here are a few few things that that I generally recommend.

One is to, first of all, just recognize as a parent that your well-being actually matters too. It feels very simple to say, but it's not so obvious to many parents who routinely put their everyone else first, you know, before them and often feel guilty about sleeping as much as they need to or making sure that they have a little downtime to actually recuperate. The second thing that I would urge parents to do is just to recognize that these small moments of outreach and conversation with other parents, where we openly share what we're dealing with, these can be lifelines for us. They can actually help us feel like we're less alone, help the other person feel that they can be more open with us, but they can give us somebody to lean on, when we have difficult times. The third thing I I would say is that there are small acts of support that we can extend to one another, which can actually help us feel like we're building a village.

So many parents are going through parenting without a village, and that is one of the biggest differences between now and a few generations ago. Right. A few generations ago, people often had neighbors and family members living close by and friends and others who could help with the the process of raising a child and and managing all that comes with that. But as people have moved around more, as we become more isolated as well as our relationship shifted from in person to online, a lot of that village has evaporated. Right?

Yeah. So how do we rebuild that village? Well, we do it in part through small acts of outreach and kindness. I'll give you an example. Today, I got up.

My wife and I got our kids ready for school. We're about to walk out the door, and then we get this message on our phone. Emergency water pipe burst. School closed today. Right?

So all of a sudden, all of these parents are they they they are wondering what do I do? The text thread, you know, with our kids' parents, all of a sudden blows up. Right? Everyone's like, oh my god. I'm literally on my way to a meeting.

I'm going here. I'm going there. I'm about to give a presentation. What do I do with my child? And what was really, amazing to see is that parents started volunteering.

Like, One parent said, hey. If anyone needs to just drop your kid kids in my house, I can take 2 or 3 kids and watch them, while you're at work. Another parent said, well, you know, I'm gonna be working from home. I'm gonna be juggling it, trying to figure it out, but I could probably have another child here, you know, if somebody needs someone to pinch hit. People just started figuring out how to help one another.

Now we that will happen because there's a crisis this morning. But there are these many crises we're facing every day. We don't have to wait for a water pipe to burst, to just check-in with a parent. Be like, hey. Do do you wanna you want me to pick up your your kid today?

I you know, we live close to each other. You can just swing by my house and pick them up, you know, afterward. Or do you want you just you could wanna come over and play for a little bit. You just take a little break for an hour, go out and do something. Like, these, again, seem like small things, but they actually make a a really big difference, you know, in the life of another parent.

So these are small things we can do to start building those bridges. And finally, the more we can actually build off of these bridges to start talking about these big issues, whether it's mental health, social media, violence, and safety, the better off we'll be. Because social media is actually a great example where we have a collective action problem. Right? If you are a parent who, as I've, you know, strongly urge parents to do, wants to delay your child's use of social media until after middle school and then reassess when they're in high school, it becomes really hard to do that, like, when every other child in your kid's class is already on social media.

Then they're coming to you saying, hey. Do you want me to feel even more lonely and left out? But if you were able to say, as I hope to one day be able to say to my kids that, hey, you're not the only one who's waiting. But I've talked to the parents of 3 of your friends in class, and they're gonna do the same thing. So the 4 of you will actually be together and hopefully maybe more in the future.

That becomes a lot easier to do. So there is strength in numbers. And the more we actually talk about these issues and game plan with each other, the better. Because the truth is it's not just with social media. Right?

Like, so many parents are feeling like, if I don't get my kid into multiple sports, multiple languages, multiple extracurriculars, then my kid's not gonna be competitive for college or they're gonna somehow be behind. Yeah. But just to, like, to be able to say to a parent, which I want every parent to know, that unstructured play is a good thing. It's not a waste of time. It's not inefficient.

It's actually what our kids need and what they don't have enough of in their life. And that if you're a parent who says, you know what? I'm actually gonna give up that, you know, extra instrument or extra sport. And in fact, I just want my child to have some time where they can be a child and read and play with other kids and explore things. That's okay.

That's actually part of what our kids need that they don't have enough of. We we certainly want to, in fact, build those bridges and connections to have those conversations not only with other parents, but for kids to actually build those villages themselves. And, you know, the creativity and magic that happens with, you know, pure boredom is lovely, and we need to, you know, sort of maximize that for sure. Vivek, you and I are, of course, linked, and connected not just as because we're physicians, but we're also Indian Americans. And I'm just curious how this particular part of your identity has really informed and, impacted your work as a surgeon general.

It's been incredibly important. Like, my parents grew up in India. My it's where my ancestors are from. I've spent a lot of time in India. I've, I got my start in public health in India, actually, working initially on HIV projects back, when I was 17 years old with my sister, and then on community health worker programs.

But, really, the most important impact that my Indian heritage has had on me, has been through the values that my parents took on from their upbringing and that they infused into my own childhood. Values that centered around the importance of friendship and community, the importance, of service, and the importance of taking care of your family. Right? These are things that my parents were raised with, and it's very interesting. My my father grew up in a small farming village in India, And he once told me a very interesting thing.

He said, you know, I never felt that sense of emptiness that something was missing in my life. I never felt that deep seated loneliness until I actually left the village and left India. Mhmm. And he said that he and it was an interesting thing to say, especially for, a person who grew up in dire poverty. Like, my father's Yeah.

Family was so poor that they didn't have enough to pay for slippers or shoes. They they had to share pencils, he and his 5 siblings, because they didn't have enough money to buy enough pencils. Like, there wasn't often enough food around the table at night. It was very hard circumstances. Yet, what he lacked in in material comforts, he had actually in community.

Like, the community in the village in like, was extraordinary. Like, neighbors looked out for each other. They took care of each other's kids. When his mother died of tuberculosis when he was 10 years old, leaving him and his sick siblings just bereft and just devastated. It was the neighbors and the village members and extended family who stepped in and became surrogate parents.

That sense of community and the commitment to serving others, which my parents really embodied through their own practice, of medicine and building a medical clinic in Miami when I was growing up, those are values that they took on from their parents, from the culture they grew up in in India, and that they passed down to to my sister and me. Yeah. Now these aren't uniquely Indian. There are many other cultures, you know, that that share these values, but they were deeply instilled in my parents, you know, through their Indian heritage. And I always see that as one of the greatest gifts, that they've given to me and my sister.

I mean, that certainly shines in, the work that you've done and and all the incredible messaging and prioritization that we talked about as surgeon general. I imagine that they also instilled your deep love of, mangoes and, of course, your self professed, Mango aficionado is what I read also. So I know you just went to India just a couple of weeks ago or or perhaps recently and, hope I know it's not season right now, but hopefully, you did have a chance to partake a little bit. Yeah. You know, it's interesting.

They they missed I mean, they loved, you know, being in the United States. They were so grateful to have their home be the United States and to be able to raise their children here. And I will say that so much of what they dreamed and hoped about in coming to the United States, that they would come to a place where people would accept them, where their children would have opportunities, where they could actually contribute and be a part of a bigger community. Like, over time, they've been able to realize those dreams, and my family will always be incredibly grateful for that. But they missed a lot, you know, about India.

One of the things they missed were the mangoes and the jackfruit and the other fruits that they had. So when they moved to Miami, they sought to recreate India in the backyard. Mhmm. And that's why to this day, we have 9 varieties of mangoes that grow in the yard. We have 6 varieties of jackfruit.

We have custard apples, seed apple, as you would know it, and Yeah. You know, many other fruit that they found in India. But I I I I would be remiss if I didn't say that. Like like, so much of, I feel like what I've been had a chance to do in my life, if not all of it, has just been a product of their vision, their affection, and their hard work. Right?

Like, without just their love and their dedication and their perseverance despite some major, major challenges, that they face in life, like, there's no way that I would have gotten, into a good school, that I would have gotten through college, because we had many crises when I was in college. There's no way I would have had the chance to to become a doctor, to serve, you know, engage in public service. Like, all of these would have been impossible without without my parents. And I often think about the journey that they have been through, where they started, my father in particular being, you know, the you know, just from a a a very poor family in a farming village in rural India Sure. To where he is now, you know, as, as a doctor who's contributing to his community in the United States.

And that delta is so big. Right. That jump is so magnificent and and and huge. In my lifetime, I will never be able to make a jump, like, that big. Right?

I will be able to hopefully contribute in ways that will be meaningful to the world. But I always look at my father, my mother, and scores of other immigrants like them, and also people who are not immigrants, but who grew for who grew up from in very humble, and difficult circumstances and created a platform for their families, to really contribute. And I just think that those are the people I look to, you know, as sources of inspiration because their quiet determination and strength, is, I think, what has made my life possible, but what I aspire to as well. Yeah. No.

The aspirations of that, of reaching those deltas, really is something to not only just reflect on, but constantly remind ourselves of.

You're listening to Trust Me. I Know What I'm Doing. After a quick break, we'll come back to our conversation with doctor Vivek Murthy, United States Surgeon General. Stay tuned.

Every story told is a lesson learned, and every lesson learned is a story waiting to be told. I'm Abhay Dandekar, and I share conversations with global Indians and South Asians so everyone can say, trust me, I know what I'm doing. New episodes weekly wherever you listen to your podcast. Hi. I'm Krish Ashok, author of Masala Lab, The Science of Indian Cooking, and you're listening to Trust Me, I Know What I'm Doing.

Hi. This is Madhuri Dixit. Hi. This is Farhan Akhtar. Hi.

This is Vidya Balan. Hi. I'm Lilly Singh, and you're listening to Trust Me, I Know What I'm Doing.

Hi there. I'm Abhay Dandekar, and you're listening to Trust Me, I Know What I'm Doing.

Let's rejoin our conversation now with the United States surgeon general, doctor Vivek Murthy. You know, I I was thinking about some of your formative experiences. You mentioned some of that already. I mean, particularly professionally involving setting up health worker education with Swastia and then and then mobilizing physicians here in the US to think a little bit more deeply about access with doctors for America. I feel like empowering individuals and educating all of us together is the real common thread and and how we connect the dots in many ways to both health issues and and sort of public service issues as well.

And yet the public and especially the WhatsApp channel threads that our Indian community is so fond of, among aunties and uncles, they they can be real vehicles of misinformation and, in fact, incredibly disempowering through social media. And so in order to think about educating and empowering and informing properly in 2,024, what do you think individuals need to what do individuals need to, in fact, unlearn about social media and perhaps even themselves to restore that that sense of empowerment? One thing just to remember is as basic as it sounds is that everything you see online is not necessarily true, and that's increasingly important to remember in an age of AI where things can often be made to seem like they're coming from official channels. The second thing I think is important to remember is given that first fact that we shouldn't be sharing information, particularly about health that we encounter online, and then we're sure that it's true. So if you're not sure, don't share.

And that's a reversal of what the default used to be, which is we shared everything unless we knew that it was egregious or definitely wrong. Well, there's a lot of uncertainty now. So if you're not sure, don't share. You may in inadvertently be be hurting others. And I think the final thing to do is just to recognize that, honestly, that that expertise really does matter, and we have to go to trusted sources to get information about important subjects, whether it's about our health and well-being or whether it's about, you know, how we invest our money or whether it's about any other important dimension of our life.

Like, we need to to go to trusted sources. Like, I I wouldn't go to my doctor for investment advice, and I wouldn't go to my financial adviser for medical advice. You know? Like, because somebody has a platform, doesn't necessarily mean that they have wide expertise. And I think very importantly, because somebody is famous doesn't necessarily mean that they have expertise.

And I do think that we I I do worry about the culture of celebrity worship that we have not just in the United States, but in many parts of the world, where we accord, I think, expertise, to people who may not necessarily have it. There's nothing wrong with being, being a celebrity or being famous. But, again, that doesn't mean, that you are necessarily equipped, to give people advice about their health or other important dimensions of their life. Yeah. You know, the value of trust that we shape and frame has evolved so much with all of these different factors and forces that those are incredible reminders.

You know, one last thought when we think about trust and and thinking a lot about all those different forces that are out there. I work with parents and grandparents and babies and toddlers and children and teens every day. And in a landscape when there are those forces, there's so many of them that are propelling distrust and stress and poor mental health and all the things that we've meander through in this conversation. In reflecting on youth particularly and, our future, what what brings you hope and joy and optimism and perhaps even accelerates that optimism in in thinking of our youth and and sort of the pathway forward beyond just the work that perhaps you or I are doing? To me, what gives me the most hope is actually spending time with young people as I do around the country and realizing that at their heart, they're so good.

They still want to really get at the heart what's gonna drive fulfillment. They still care about other people. They still wanna contribute to their community. They wanna be a part of solving big problems. They don't wanna just sit aside and observe them.

This is the the deeper instincts, that I find as I talk to young people around the country. Now that doesn't mean that they always necessarily find themselves acting in that way. They may they're also like all of us, you know, adults. They're they're subject to and influenced by the environment around them, you know, and it's often an environment that can be disempowering. They can often tell them problems are too big to solve, that the world is too broken to fix, or that their compassion is naive, you know, and not something, that could be a source of strength or power to them.

And these are also messages the young people tell me that they get. But I think that the instincts that young people have, that I think actually all people have, are generally good. I was talking the other day to, to a a man who was describing to me how he got a flat tire, you know, on the road when he was driving in a part of the country that he was not familiar with at all. And, you know, a guy pulled up behind him in this big truck with all kinds of bumper stickers that made him scared because, somebody who clearly had very different views from him had a lot of political bumper stickers on his Sure. On his car.

But the guy pulled up behind him on the side of the road, and he's thinking, oh my god. What's gonna happen? The guy jumps out of his car and says, hey. I noticed that you had a flat tire. Can I help you?

I was you know, let me help you get get on back on the road again. Yeah. And they had this wonderful interaction. And I was reminded when I heard that story that, you know, despite all these things that we hear around us about how terrible people are, despite the the voices around us that are seeking to profit from our division and despair, and are just feeding that more and more, people genuinely, their two instincts actually are to be kind or to look out for one another or to be good. And that's what ultimately gives me hope.

And I think if we can lift up more examples of people serving in that way, if we can help young people understand that those instincts are what make people valuable, what make them worthy or worthy of cultivation, and not things to be put aside or shunned as naive, then I think we have a real shot at building the kind of society where people do look out for each other, where we actually rebuild the social fabric of our country, and people can exist in communities and not alone managing all the challenges of life by themselves. I wonder if we are just prone because of the climate that we live in to constantly underestimate as opposed to and and make those assumptions instead of perhaps especially with the example you just provided instead of giving grace to what's possible and and be, you know, mindful of of what those opportunities are and not succumb to the underestimation of either generations or people who are out there. Yeah. This is I I think the part of what makes us underestimate, people's capacity for goodness, frankly, is our digital and our news experience. You know, like, so many young people tell me, like, high school students, college students I encounter around the country and even outside the country.

They tell me, how am I supposed to feel good about the world when my phone is constantly vibrating with the negative headlines that are telling me everything that's wrong with the world? And I get and it's not that there aren't things that are wrong in the world. It's not that we should be oblivious to the challenges in front of us, but our messaging has become so skewed that the vast, vast majority of what we're consuming is about all the negativity. We rarely hear, about the neighbor who's stepping up to care, for their neighbor who's sick or who lost their job. We're not hearing, nearly as much about the students who are stepping up to help peers in high school, you know, who are struggling with their mental health.

We're not hearing about the good, like, in people nearly as much. And so we have a misunderstanding, I think, a misrepresentation of that balance between good and hardship in the world. So I think that if we really wanna restore that balance, part of what we've got to do is stop living our lives online as much as we are and start living it in the real world, talking to our neighbors, talking to, the parents of kids in our class, being open and honest about what we're going through and that recognizing that that will allow other people to do the same. We have to get engaged in in service in our communities, helping whether it's helping our neighbor or coworker with during a moment of need or volunteering, in organizations that help to serve the broader community. It's our engagement in service.

It's our building of relationships in the real world. This will ultimately help us come back to who we really are, which is people who are good, who are kind, who look out for each other, and whose capacity for generosity is really quite extraordinary. And that's what we have an opportunity, I think, to rebuild. Well, those opportunities certainly exist in the health professional space and and what keeps us energized and with so much joy and optimism and and the extraordinary word that you mentioned probably pretty befittingly describes the work you're doing, and we're so grateful for your service. Doctor Vivek Murthy, thank you so much for for joining for this conversation.

I hope we can connect with you again down the road. Well, thanks so much. I'm really glad that we did this, and thanks for helping to bring positive messages to your to your listeners, you know, on a regular basis. It's so needed right now. Appreciate you.

Thank you so much, Doctor Murthy, for all that you do. Shout out to my parents, Sharad and Smita Dandekar on their wedding anniversary and for their impeccable Dandekaring skills over the last 56 years. Big thanks to Sunny K and Dave C as I got to meet the last third of your stellar moai. Shout out also to Alivia Erwin for all that you're doing to help fight Alzheimer's disease, and please visit Alivia's page to donate and learn more as you can find in the show notes. Till next time.

I'm Abhay Dandekar.